Comics + America

“Comics and Contemporary America” (Spring 2021) was an upper-level, online English course intended for 40 students. I assumed those students had no previous experience reading or studying comics at university, so I covered some foundations to get us started: terms, techniques, and histories that would help us to better grasp the assigned materials. Then we focused on comics published in the 21st century and how they comment on, or correspond with, contemporary American culture. Those comics included Ms. Marvel, Vol. 1: No Normal (2014), Victor LaValle’s Destroyer (2017), Monstress, Vol. 1: Awakening (2016), Special Exits (2010), and Daytripper (2010; published by DC Comics but written and illustrated by Brazilian artists, Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá).

This course was my first attempt at teaching comics for an entire term rather than including a graphic novel or two on an American fiction or media studies syllabus. I revised my approach to assignments accordingly, situating each prompt in a hypothetical scenario grounded in concrete details. Here are two examples: 1) “The Canadian Society for the Study of Comics invites papers on comics in the post-secondary classroom. They are looking for focused arguments (750-1000 words), informed by classroom experiences, for particular comics that should be taught and studied in the 2020s. These papers will be collected and published on the Society’s website. There may also be a conference panel on the topic. Intrigued, you decide to submit a paper.” 2) “Imagine you occasionally produce audio and video content for an online Canadian publication about comics and comics culture. It’s June 2017, and one of the venue’s editors has asked you to review Awakening, the first volume of Monstress. It’s a relatively short review. They’ve given you no more than five minutes. They are also a bit behind on this one. Awakening was published in July 2016, and it collects issues 1-6 of Monstress, which was first published in late 2015. But you take the gig.” My interest in roleplaying games is not mildly apparent in these instructions.

Students could choose one of two prompts for each assignment, but both paths nudged them to consider how fiction and criticism are mediated by various factors, from context and intended audience to genre and style to cultural values and the complex dynamics between image and text. One thing that struck me was how compelling and insightful student responses can be when the particular conditions of the writing situation, even if speculative, are communicated to them. This realization probably isn’t news to writing experts, yet “Comics and Contemporary America” rendered it palpable to me nearly ten years after arriving at UVic. The hypothetical scenarios aided the class, too, as they offered us shared spaces to picture and inhabit while we met online during a pandemic.

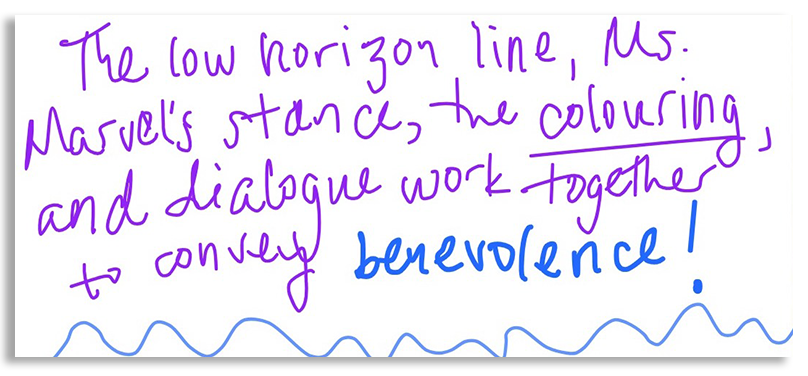

The official description of the course is below, together with links to the course website and syllabus. Many thanks to Faith Ryan for teaching this course with me, and to Molly Butler and Fiona Thompson for giving me permission to include images of their work here. The image above is a panel Molly made as an exercise in imitating the style of another comic: in this case, the style of Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. The image below captures one of many ways Fiona annotated Ms. Marvel; as part of a hypothetical scenario, Fiona’s annotations were intended to engage high school students in how comics create superhuman characters and express superhuman powers.

Comics and Contemporary America

Spring 2021 | UVic English 425 | Undergraduate course for 40 students

Links: course website (HTML); syllabus (PDF); prompts (HTML)

Comics are integral to the study of America and American fiction today. They experiment with representation, play with genre, speak truth to power, and prompt important conversations about art and culture. We’ll discuss these topics and more by engaging the politics and aesthetics of 21st-century comics and sampling various critical approaches to them. You’ll learn how comics work, why they matter, and how to write about them for popular and academic audiences.

Aims

You’ll have the opportunity to:

- Demonstrate various strategies for approaching comics. You’ll develop a vocabulary for talking about them, too.

- Interpret comics in the context of fiction and contemporary America (2000 to the present) while attending to some histories of comics and their genres.

- Identify techniques people use to makes comics and explain why the aesthetics of comics matter today.

- Articulate the relationship between comics and power, including the subversive and normative elements of comics.

- Communicate critically about comics and with them. This means you’ll treat comics as not only evidence or examples (communicating about comics) but also ways of experiencing and understanding the world (communicating with comics).

We will assume you’ve no previous experience studying comics in an academic setting.

About Us

My name is Jentery Sayers (he / him / his; jentery@uvic.ca). I’m a settler scholar and associate professor of English and Cultural, Social, and Political Thought (CSPT) at UVic. I also direct the Praxis Studio for Comparative Media Studies. I did my MA and PhD in English at the University of Washington in Seattle, and I grew up in Richmond, Virginia, where I got my BA and BS at Virginia Commonwealth University. I’ve been at UVic since 2011, and I teach courses on American fiction, media and cultural studies, and experimental prototyping. This is the 35th class I’ve taught here, but only my third online. I’ll be learning a bit as we go. Thanks for your patience.

And my name is Faith Ryan (she / her / hers). I’m a settler on unceded Lekwungen and WSÁNEĆ lands, and I am grateful for the years I’ve been able to study here. I’m a graduate student in English at UVic, and I did my BA at UVic as well. I’m originally from Ogden, Utah, but I spent most of my high school years in the lower mainland BC. I like contemporary Canadian and American fiction and approaching culture, in all its forms, from a disability studies perspective. Feel free to reach out over the term, even if you’re unsure whether it’s something I can assist you with. If it isn’t, then I can point you in the right direction. I hope you enjoy the course!

Assignments

We are asking you to respond to four prompts this term, and we’ll invite you to revise one of those responses. Each response will constitute 25% of your final grade.

There are no quizzes, exams, discussion forums, or student presentations in this course. There is no participation mark, either. Both of us will mark your responses to the prompts and provide feedback on your work.

All the prompts are included in this outline, and due dates are provided in the schedule. Please submit each of your responses via Brightspace. We cannot accept submissions by email.

Please note that each prompt affords two ways to respond to it, and not all responses are academic essays. You should pick one of the two options in the prompt and then consider your audience as well as the assignment’s aims (mentioned in the prompt) as you respond. We’ll use the aims as guides to mark your responses.

Workload

One of the most important things to know about this course is that we’ll opt for care in every instance. If the workload becomes too much, or we’re juggling more than we should, then we’ll cut materials, including assignments, as we go. We’ve planned for the maximum in advance, under the assumption that we won’t get to everything. And that’s totally fine.

We suggest dedicating an average of 3 to 5 hours of study each week to this course, plus 1.5 hours for the weekly meetings. To frame expectations and decrease overwork, we assign in the schedule a number of recommended hours to each week of the course, and we communicate progress in terms of weekly steps (0-14) toward completing the course, partly because online learning makes time weird for us all, and focusing on anything is a struggle during a pandemic.

Of course, 3 to 5 hours per week is only a guideline. You may find that you need (or want) more or less time depending on the activity, your preferences, what you can manage during a given week of life and online learning, and your own familiarity with the comics and concepts involved.

Comics

Here’s a list of the comics we’ll read this term. They’re available at the UVic Bookstore. You are also welcome to read them as ebooks on a tablet or in your browser, if you’d prefer. You should spend no more than $117 (before taxes) on these books. Purchasing used copies or ebooks, or relying on subscription services, will save you money. (Ebooks may total as little as $47 for this course, saving you up to $70 before taxes.)

- Ms. Marvel, Vol. 1: No Normal (2014), by G. Willow Wilson, Adrian Alphona, and Jake Wyatt

- Victor LaValle’s Destroyer (2017), by Victor LaValle and Dietrich Smith

- Monstress, Vol. 1: Awakening (2016), by Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda

- Daytripper (2010), by Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá

- Special Exits (2010), by Joyce Farmer

You may want to pick up Hillary Chute’s Why Comics? From Underground to Everywhere (2017) and/or Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art (1993), too. We’ll refer to both throughout the term, but having your own copies won’t be necessary.

We will also share examples of work by some (or perhaps all) of the following people during our meetings: Weshoyot Alvitre, Rosaire Appel, Kyle Baker, Lynda Barry, Alison Bechdel, Joyce Brabner, Charles Burns, Emily Carroll, Ezra Claytan Daniels, Eleanor Davis, Kelly Sue DeConnick, Will Eisner, Sigrid Ellis, Emil Ferris, Matt Fraction, Neil Gaiman, Dave Gibbons, Kieron Gillen, Phoebe Gloeckner, Roberta Gregory, Joy Harjo, the Hernandez brothers, John Jennings, Stephen Graham Jones, Tom King, Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, Jeff Lemire, Sloane Leong, Erik Loyer, David Mazzuchelli, Scott McCloud, Jamie McKelvie, Carla Speed McNeil, Mike Mignola, Alan Moore, Robert Morales, Brennan Lee Mulligan, Molly Ostertag, Harvey Pekar, Ed Piskor, Greg Rucka, Gail Simone, Nick Sousanis, Art Spiegelman, Frank Stack, Fiona Staples, Brian K. Vaughan, Tillie Walden, Chris Ware, Bill Watterson, Delicia Williams, and Gene Luen Yang.

Finally, near the end of the term, we’ll read Raymond Williams’s “The Analysis of Culture” (1961), available via Brightspace in PDF; in March, we’ll watch Erik Loyer’s “Timeframing: Temporal Aesthetics in Digital Comics” (2020); and, in February, we hope to screen, White Scripts and Black Supermen: Black Masculinities in Comic Books (2010), which was produced, written, and directed by Jonathan Gayles. In early February, we will draw lecture material from Stuart Hall’s “Notes on Deconstructing ‘The Popular’” (1981) and Dr. Julian Chambliss’s work on comics and the comic book industry. We will make a PDF of Hall’s essay available to you, and Dr. Chambliss’s videos are already available on YouTube.

For more information, see the syllabus for the course.

The featured image is a panel care of Molly Butler. The main image is an annotation of Ms. Marvel care of Fiona Thompson. Both images used with written permission. I created this page on 25 January 2022 and last updated it on 30 January 2022.